There’s nothing quite as exciting for me as spotting a monarch butterfly in the garden. After moving to Lake Livingston in late 2012, it was two years of reworking my gardens to include lots of plants to attract the pollinators like butterflies and hummingbirds, before the first monarch showed up.

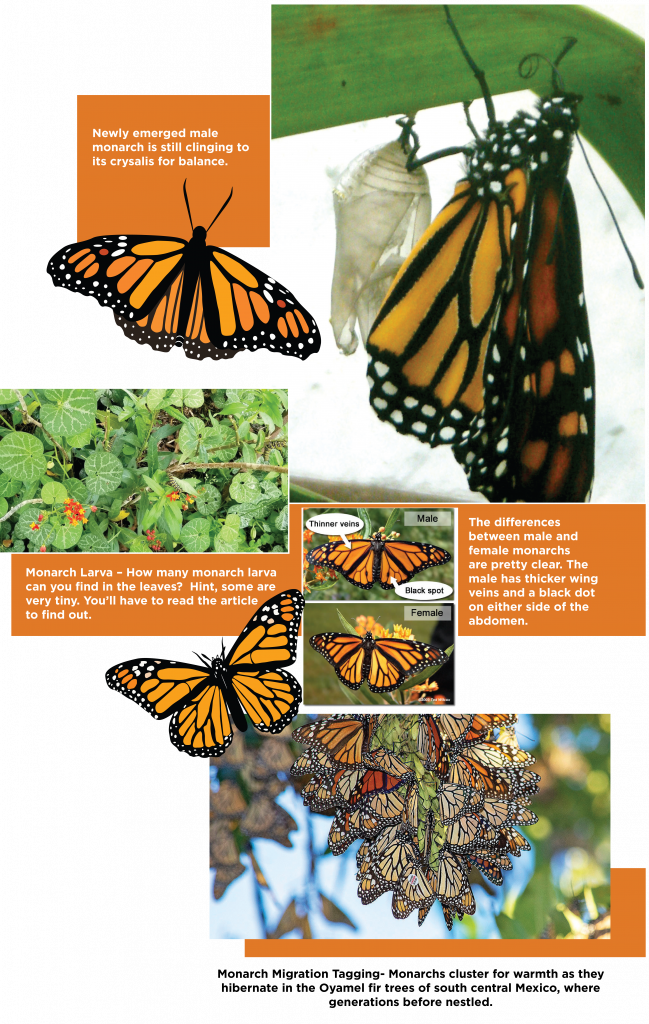

Just a few weeks ago, without seeing a monarch, I found several of their larvae happily munching my native swamp milkweed clean. Then they disappeared. Try as I might, I rarely find a single chrysalis among my dense plantings. Still, I catch a glimpse a newly emerged monarchs hanging under a branch, drying its wings.

It’s pretty easy to tell the male from female monarch. Males have a small black spot on the top surface of the hindwing and their wing veins are thinner.

Living in east Texas, we see monarchs pretty much all year. We’re on the final hop for the migratory generation, so we catch them fluttering off to the primary hibernation site, a grove of Oyamel fir trees in south central Mexico where generations before spent their winters. Those west of the Rockies migrate to Pacific Grove, CA where they hibernates in eucalyptus trees.

Living in east Texas, we see monarchs pretty much all year. We’re on the final hop for the migratory generation, so we catch them fluttering off to the primary hibernation site, a grove of Oyamel fir trees in south central Mexico where generations before spent their winters. Those west of the Rockies migrate to Pacific Grove, CA where they hibernates in eucalyptus trees.

The only hibernating butterflies, monarchs go through four or five generations each year, but only one generation migrates. The rest just stay in place along the migratory path, living out their short lives mating and laying eggs. The non-migrators have a lifespan of only two to six weeks. During the migration they can live longer, mostly because they actually hibernate for several months, but rarely through a round trip.

During their short lives, males and females find each other, mate, and most females lay many eggs each day, provided she finds some of the more than 140 species of milkweed (Asclepias). The most common milkweed in southeast and east Texas has orange and yellow flowers and can fill a yard by profusely seeding itself.

Female monarchs lay their pinhead sized white eggs on the undersides of the milkweed’s leaves.

The eggs hatch after a few days, when the caterpillars are less than half an inch long. They feed ravenously, completely defoliating the milkweed, until they’re about two inches, and then seek a safe place to form their chrysalis for the most dramatic of transformations.

The eggs hatch after a few days, when the caterpillars are less than half an inch long. They feed ravenously, completely defoliating the milkweed, until they’re about two inches, and then seek a safe place to form their chrysalis for the most dramatic of transformations.

As beautiful as the monarch butterfly is to watch, the larvae are spectacular on their own. They stay on the underside of the leaves until they’ve grown a bit. Their bright black, white and yellow rings are a bit inconspicuous, but birds don’t find them very tasty. They didn’t find the five that appeared in the group photo in this article.

The entire mating, egg laying, larva, and chrysalis period takes about two months. The migratory generation, the last of the year, is the largest with the most losses before it reproduces after hibernation. The newly emerged butterflies don’t mature completely before they migrate. While they look like normal adults, they are barely into puberty.

Although beautiful, the tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) houses a parasite called Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE) that infects the larva and hinders or stops its transformation. Adult monarchs can carry it from plant to plant, adding to the spread. Monarch protection organizations recommend cutting the tropical milkweed to the ground in mid-fall to force it to go dormant and then replace it with the parasite-resistant native milkweeds. These are becoming available at native plant nurseries or from seed catalogues.

Development across the U.S. has taken a toll on the meadows where monarchs found varieties of milkweed. Groups like MonarchJointVenture.org and SaveOurMonarchs.org are rich with information about monarch food sources and the issues facing survival of the amazing pollinators.

Learn more about helping monarch butterflies by joining a chapter of the Texas Master Naturalist or Texas Master Gardeners. Piney Wood Lakes Master Naturalist serves members across Polk, San Jacinto, Trinity, and Tyler Counties with volunteer opportunities, educational resources and conservation projects. txmn.org/pineywoodlakes SJC Master Gardeners serves members in San Jacinto and Polk Counties, sharing their time, knowledge, and expertise to improve the quality of life for neighbors and area visitors.