Bald Eagles

Bald eagles are very distinctive with their white head and tail feathers and dark brown feathers covering the rest of their body. They are powerful, large birds of prey, with females weighing as much as 14 pounds and having a wingspan of up to 8 feet. As with most raptors, males are somewhat smaller, so they tend to weigh 7 to 10 pounds with a wingspan closer to 6 feet. Young eagles are mainly dark brown and lack the white “bald” heads until they are four to five years old, so they are sometimes confused with golden eagles (although in our area of Texas, golden eagles are not indigenous). There is a distinction between the two species, though, even when they are young. Bald eagles have feathers only at the tops of their legs while the legs of golden eagles are feathered all the way down. Bald eagles prefer to live near water where they can find fish, their staple food. They will also feed on waterfowl, turtles, rabbits, snakes, and other small animals and carrion. They require larger trees for perching and nesting sites. In colder climates where water ices over, bald eagles will migrate south to find winter sources of food.

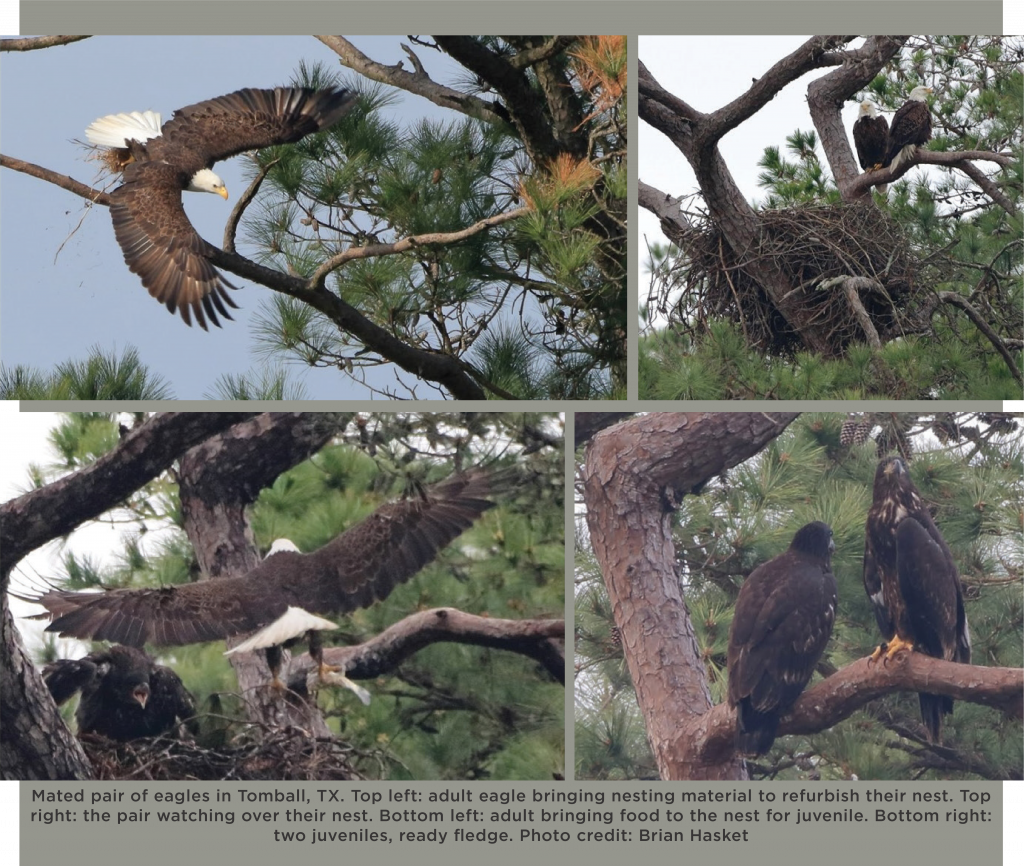

Eagles mate for life. They prefer the tops of large trees to build nests, which they typically use and enlarge each year. Some nests may reach 10 feet across and weigh a half ton. Occasionally pairs will have one or more alternate nests within their breeding territory. In areas lacking tall trees, eagles will nest on cliffs or the ground. Bald eagles typically lay one to three eggs a year (in our area, usually November-January). The eggs hatch approximately 35 days later in the order they were laid. Both parents tend to the young and will bring food back to the nest. The eaglets are flying within three months and are independent and hunting on their own by four to five months of age. If food is scarce, the older eaglets sometimes push younger siblings from the nest. Disease, lack of food, bad weather, and human interference unfortunately kills many eaglets. It is thought that about 30% of eaglets do not survive their first year of life. Although young eagles travel great distances, they generally return to breed within 100 miles of the place they were raised. Bald eagles typically live 15 to 25 years in the wild.

Forty years ago, bald eagles were in danger of extinction throughout most of their range. Habitat destruction, illegal shooting, and the contamination of their food sources (largely due to the pesticide DDT) decimated the eagle population. In 1963, there were thought to be only 487 nesting pairs of bald eagles left in the 48 contiguous United States. In 1967, bald eagles were listed as endangered south of the 40th parallel (under the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966). The use of DDT was banned in 1972. Then in 1978 (under the Endangered Species Act of 1973) bald eagles were listed as endangered throughout the lower 48 states (except in Michigan, Minnesota, Oregon, Washington, and Wisconsin where they were designated as threatened). Due to these protective measures, the bald eagle population rebounded greatly, and in 2007 they were removed from the list of threatened and endangered species. However, since the bald eagle was chosen as a national emblem of the United States by the Continental Congress of 1782, they are still a protected species under The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act of 1940, which is a federal statute. This makes it illegal to pursue, shoot, shoot at, poison, wound, kill, capture, trap, collect, molest or disturb bald eagles.

The good news is the number of bald eagles in the lower 48 states has quadrupled in the last 12-15 years. Based on the most recent population figures, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that there are approximately 316,000 eagles with 70,000 nesting pairs currently in the 48 contiguous states. The bad news is that even though their numbers have increased, many eagles still face grave dangers. Habitat destruction, poaching, pesticides, wind farms, electrocution (due to power lines), and poisoning are the main threats to the eagle.

We can all do our part to help protect these magnificent birds, as well as all birds of prey. Whenever possible, use natural pest control products. Poisoning is a huge problem affecting eagles as they will scavenge on carrion. Poisons and baits put out to control pest animals may later be ingested by eagles scavenging on those same animals (rat poison, etc.). Lead poisoning also is a major problem in eagles. If they ingest fish or other meat contaminated with lead, the high levels of lead will kill the eagle. Lead fishing sinkers and lead ammunition are the main culprits. Hunters can help by: using only non-toxic shot for all small game shotgun hunting (lead shot is already prohibited for waterfowl hunting but optional for other small game); using non-toxic slugs or bullets for deer hunting; if lead ammunition is used, recover and remove all shot game from the field; hide gut piles and remains of butchered carcasses by burying or covering with rocks and/or brush; remove slugs, bullets or fragments and surrounding flesh from any carcass remains left in the field. If fishing, use non-lead sinkers. These measures will prevent eagles, hawks, owls, and other animals from scavenging on lead-contaminated meat or fish.

As very large birds of prey, it generally takes something quite serious to bring an eagle down to the point where they are found on the ground by people. Quite often by the time they are found it is too late to save them. Friends of Texas Wildlife is currently caring for a male bald eagle found on the ground and unable to fly in Polk County. Due to unknown trauma, the eagle has an injury to his right shoulder. This eagle will be with us for at least four to six weeks before we can even flight test him, and then (hopefully) four to six weeks more while he regains his flight strength. If the injury leaves him unable to fly, we will have to find him a permanent sanctuary, which is no easy task. Due to their size and dietary preferences (lots of fish!) eagles are extremely expensive to care for. Since no wildlife

rehabilitation costs are covered by any local, state, or federal agencies (despite eagles being a protected species) donations to help with his ongoing care are both necessary and much appreciated. You can donate to assist with his care at www.ftwl.org and follow the eagle’s story and progress by viewing our Facebook page.

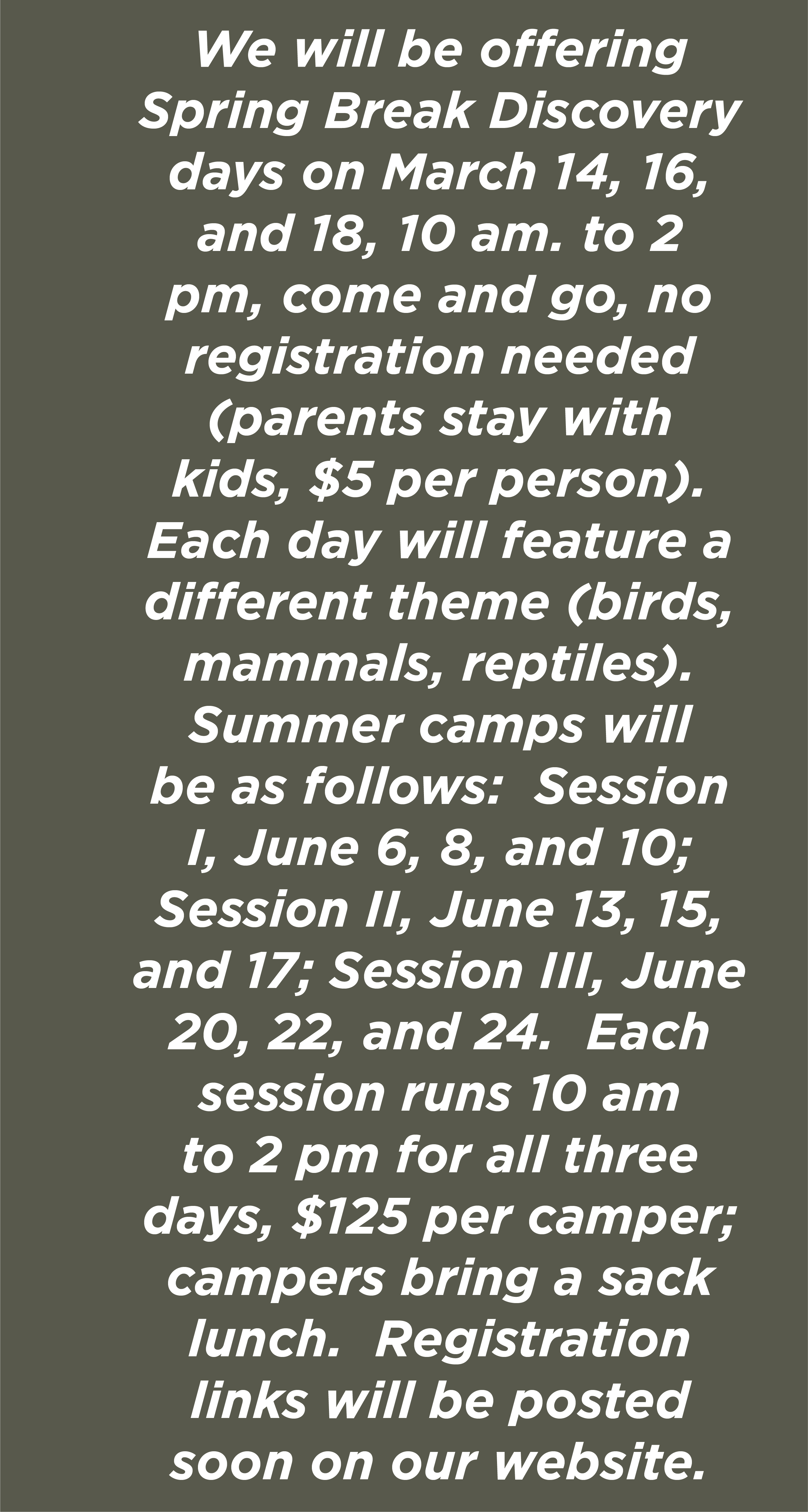

To learn more about what we do and view pictures of the many of the animals we assist, please visit our Facebook page at www.facebook.com/SavingTexasWildlife. Details and specifies-specific flowcharts regarding how to help found animals can be viewed on our website at www.ftwl.org (click on “Help and Advice”). These charts are extremely helpful to determine if an animal truly needs rescuing or not. If you need assistance with a wildlife animal you have found, please call us at 281-259-0039 or email us at [email protected]. We offer many educational programs (including camps, birthday parties, educational presentations, and Second Saturdays). Our educational visitor’s center is open the second Saturday of each month from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., located at 29816 Dobbin Hufsmith Road, Magnolia, Texas, so the next one will be Saturday,

February 12 ($5 per person, kids 3 and under are free).